For Esme With Love And Squalor Text Pdf

I agree with Al that it is not dated. As to the gift of the watch, Barb, doesn't it make X a kind of symbolic father to these two kids who parents have perished?

If so, Corporal X is certainly in no condition to assume such a role, however symbolic. As to the recovery of Corporal X, I'm not sure how deep it runs.

The invasion of contact with love it. Squalor symbolism, for esme with love and squalor pdf. And squalor full text, for esme with love and squalor. Explaining his love for one story, Wood wrote that it's the kind you want to read aloud to someone. If I had to pick a few stories that meet Wood's assessment, one of them would have to be Salinger's tender For Esme With Love and Squalor.

Six years later, after a long correspondence with Esme to which we are not privy, X seems angry and bitter. He happily receives an invitation via 'air mail.' I know it's 1950 but air mail for me has a lofty ring to it. And his initial exuberance is soundly squashed after a discussion with his 'breathtakingly levelheaded' wife. His elderly (58) mother-in-law, Mother Grenchen, figures into the mix. In the second paragraph the narrator makes absurd assertions, suggesting that the groom will become 'uneasy' to learn about 15 minutes of tea-sipping six years earlier when his bride-to-be was 13.

And if the groom is uneasy, 'so much the better.' Anger and bitterness. More to the point, it is childlike and childish. Now that X is 25 or 26 and Esme is 19, the romantic fantasy can gain traction (except for a certain unworthy groom). Thankfully, a breathtaking levelheadedness puts it to rest. In England X witnesses the innocence and wisdom of children. Choir practice in the church becomes a near religious experience that could have induced some to 'experience levitation.'

Download Willem EPROM Programmer + schematic + layout - Find where to buy EPROM 27C64, 27C128, 27C256, 27C512, 27C010, 27C020, 27C0 M27C1001. Willem eprom programmer schematic.

Moving on to France he sees (and possibly participates in) terrible atrocities that only adults are capable of. To come back from that shell-shocked breakdown he may have needed to return somewhat to a certain innocence and naivete. Adulthood sucks. For me those first two paragraphs depict a man-child. I need help with the first sentence of the second paragraph.

All the same, though, wherever I happen to be I don't think I'm the type that doesn't even lift a finger to prevent a wedding from flatting. Also, I need help with squalor. Where, precisely, is it? Yes Barb I like that take on the watch.

It's a broken watch (that may and may not still be ticking-X is afraid to find out). Watches, especially broken watches often symbolize time or the stoppage of time and deep metaphysical problems that send me scurrying, crablike, for my stash of Excedrin. Beyond the symbolism of broken men, it represents recovery as written by Esme in her letter: but this one is extremely water-proof and shockproof as well as having many other virtues among which one can tell at what velocity one is walking if one wishes. I am quite certain that you will use it to greater advantage in these difficult days than I ever can and that you will accept it as a lucky talisman.

Looking back, Esme mentions in her letter that she did not remember X wearing a wristwatch. Well, he was wearing one. Then, after synchronizing my wristwatch with the clock in the latrine, I walked down the long, wet cobblestone hill into town. Latrines don't generally have clocks. I don't get it. But I know that everything in this carefully crafted piece has meaning. As to squalor, I think wretchedness is a good synonym.

My Webster's dictionary says, 1. Dirty or wretched in appearance. Morally repulsive, sordid. I'm sure that can be attributed to warfare but somehow it doesn't quite fit. Of course, I've never been there. I don't think Esme knew the definitions of many of her ten-dollar words.

Some of them work, some don't. She seemed to be tossing big words around to disguise her own emptiness over the loss of her parents which was evident in her damp palms and bitten fingernails. I wonder how much of that incredible dialogue was accurately narrated. She was Esme (with a romantic accent over the 'e'). Yet she signs her letter to Corporal X with the rather mundane moniker of Esma. I think it is interesting to compare his interaction with and letter from Esme to the letters he received from his wife and brother. Letters about how some local shop back home no longer provided good service or asking him to send home loot for the kids were meaningless or maybe even insulting to him.

Even Z, his companion who lived through many of the same experiences as him, misread him and couldn't help him by talking about his girlfriend and Bob Hope. Esme, on the other hand, seems prescient because she recognized that he was not like the other soldiers and specifically requested that he share squalor with her.

In my opinion, that's exactly what he needed to begin his recovery. She somehow knew what kinds of things he might run into and that she might be able to help him somehow. When he read her letter I think he remembered the vulnerability and trauma that she and her brother experienced losing their parents and how they were overcoming it and that was somehow enough for him to begin recovering his faculties. This interpretation makes her a guardian angel of sorts. Flag Abuse Flagging a post will send it to the Goodreads Customer Care team for review. We take abuse seriously in our discussion boards. Only flag comments that clearly need our attention.

As a general rule we do not censor any content on the site. The only content we will consider removing is spam, slanderous attacks on other members, or extremely offensive content (eg. Pornography, pro-Nazi, child abuse, etc). We will not remove any content for bad language alone, or being critical of a particular book.

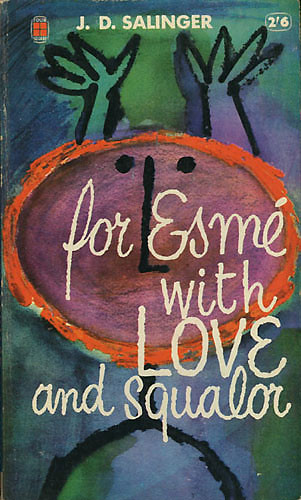

'For Esmé—with Love and Squalor' is a short story by J. D. Salinger. It recounts a sergeant's meeting with a young girl before being sent into combat in World War II. Originally published in The New Yorker on April 8, 1950,[1] it was anthologized in Salinger's Nine Stories two years later (while the story collection's American title is Nine Stories, it is titled as 'For Esmé—with Love & Squalor' in most countries).

The short story was immediately popular with readers; less than two weeks after its publication, on April 20, Salinger 'had already gotten more letters about 'For Esmé' than he had for any story he had published.'[2] According to biographer Kenneth Slawenski, the story is “widely considered one of the finest literary pieces to result from the Second World War.[3] Author Paul Alexander calls it a 'minor masterpiece'.[2]

When Salinger submitted the story to The New Yorker in late 1949, it was at first returned, and he then reedited his manuscript, shortening it by six pages.[4]

Plot[edit]

The story begins with the narrator needing to respond to a wedding invitation that will take place in England, and which the narrator will not be able to attend, because the date of the wedding conflicts with a planned visit from his wife's mother. The narrator does not know the groom, but he knows the bride, having met her almost six years earlier. His response to the invitation is to offer a few written notes regarding the bride.

The first of the two episodes the narrator relates occurs during a stormy afternoon in Devon, England, in 1944. A group of enlisted Americans are finishing up training for intelligence operations in the D-Day landings. He takes a solitary stroll into town, and enters a church to listen to a children's choir rehearsal. One of the choir members, a girl of about thirteen, has a presence and deportment that draws his attention. When he departs, he finds that he has been strangely affected by the children's 'melodious and unsentimental' singing.

Ducking into a tearoom to escape the rain, the narrator encounters the girl again, this time accompanied by her little brother and their governess. Sensing his loneliness, the girl engages the narrator in conversation. We learn that her name is Esmé, and that she and her brother Charles are orphans – the mother died, the father killed in North Africa while serving with the British Army. She wears his huge military wristwatch as a remembrance. Esmé is bright, well-mannered and mature for her age, but troubled that she may be a 'cold person' and is striving to be more 'compassionate'.

In the next episode, the scene changes to a military setting, and there is a deliberate shift in the point-of-view; the narrator no longer refers to himself as “I”, but as “Sergeant X”. Allied forces occupy Europe in the weeks following V-E Day. Sergeant X is stationed in Bavaria, and has just returned to his quarters after visiting a field hospital where he has been treated for a nervous breakdown. He still exhibits the symptoms of his mental disorder. 'Corporal Z' (surname Clay), a fellow soldier who has served closely with him, casually and callously remarks upon the Sergeant's physical deterioration. When Clay departs, Sergeant X begins to rifle through a batch of unopened letters and discovers a small package, post-marked from Devon, almost a year before. It contains a letter from Esmé and Charles, and she has enclosed her father's wristwatch - 'a talisman'- and suggests to Sergeant X that he 'wear it for the duration of the war'. Deeply moved, he immediately begins a recovery from his descent into disillusionment and spiritual vacancy, regaining his 'faculties'.

Analysis[edit]

As the war receded in memory, America was embracing an 'unquestioned patriotism and increasing conformity',[3] and a romantic version of the war was gradually replacing its devastating realities. Salinger wished to speak for those who still struggled to cope with the 'inglorious' aspects of combat.[3]

'For Esmé—with Love and Squalor' was conceived as a tribute to those Second World War veterans who in post-war civilian life were still suffering from so-called 'battle fatigue' – post-traumatic stress disorder.[3] The story also served to convey to the general public what many ex-soldiers endured.

Salinger had served as a non-commissioned officer of intelligence services at the European front – the narrator 'Sergeant X' is 'suspiciously like Salinger himself'. The story is more than merely a personal recollection; rather, it is an effort to offer hope and healing – a healing of which Salinger himself partook.[5] Slawenski points out that “though we may recognize Salinger in Sergeant X’s character, [WWII] veterans of the times recognized themselves.'[5]

In popular culture[edit]

In Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events and the subsequent Netflix series, Esme Squalor's name is a reference to this short story.

The track 'Letters & Packages' from American Football (band)'s American Football EP (1998) contains many lyrical references to this short story. Aahatein mtv splitsvilla 4 theme song agnee band free download.

We Are Scientists' 2006 album is titled 'With Love and Squalor'.

Abandoned film version[edit]

In 1963, film and TV director Peter Tewksbury approached Salinger about a making film version of the story. Salinger agreed, on condition that he himself cast the role of Esmé. He had in mind for the role Jan de Vries, the young daughter of his friend, the writer Peter de Vries. However, by the time that Salinger and Tewksbury had settled on the final version of the script, Jan had turned eighteen and was considered by Salinger to be too old for the part. The film was never made.[6]

References[edit]

- ^Salinger, J. D. “For Esmé—with Love and Squalor”. The New Yorker. April 8, 1950. P. 28.

- ^ abAlexander, Paul (1999). Salinger: A Biography. Los Angeles: Renaissance. ISBN1-58063-080-4. p. 144-5.

- ^ abcdSlawenski, 2010, p. 185

- ^Slawenski, 2010, p. 184-185

- ^ abSlawenski, 2010, p. 188

- ^Jill Lepore, 'Esmé in Neverland - The film J.D.Salinger nearly made', The New Yorker, November 21, 2016.

Bibliography[edit]

- Slawenski, Kenneth. 2010. J.D. Salinger: A Life. Random House, New York. ISBN978-1-4000-6951-4